I must have spent the night of July 1-2, 1961 in Salt Lake City, in a bed in a small YMCA on a downtown side street. That makes sense. I remember getting up early in the morning there, reaching the outskirts of the city by about 8 a.m. and picking up a ride, and then another fairly quickly. I look at the map of that area now and I figure I could have made it to that highway crossroads in southern Idaho by noon.

An ash tree reaches for the sky in the Hope Bay Forest

I remember being hung up there unable to get a ride for maybe two hours. There were no trees and the junction of the two highways was at the top of a plateau from which the highways fell away in several directions. And after a while it was too hot standing under the sun so I walked over to a truck stop about 100 yards away. There was a counter with bar chairs and some tables. A clean-cut, casually dressed man who looked to be in his mid-30s was eating his lunch at the far end of the counter. A couple of truckers sat talking at a table. I noticed there was a sign on the wall above the counter that said “we reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.” I was just 18 at the time, so what did I know, and when the large man in a white apron behind the counter asked me what I wanted I ordered a coffee and inquired about the sign.

It wasn’t just aimed at Negroes; it was for anyone they didn’t for any reason want to serve, he said in a friendly enough, open sort of way. Fortunately, I had sense enough not to say anything more about it and started drinking my coffee.

After a while the man at the end of the counter finished his lunch. I had noticed him looking at me with some casual interest. He got off his chair and walked past me to the cash register just down the counter from where I was sitting. He paid his bill and then turned to me and asked if I wanted a ride.

“I saw you out on the highway thumbing when I came in,” he said. He seemed like a nice guy. I like to think even then I had good instincts for people. That’s why when I spent the night in an RCMP jail cell in Indian Head, Alberta later that summer I don’t think I slept a wink because the guy in the cell with me looked like a real bad character. (By the way, back then if you didn’t have anywhere else to stay “on the road” you could bum a jail-bed. We had both done the same thing. Just so you know.)

“I sure would,” I said. “I was having a hard time getting a ride.”

“Where you heading?”

“The west coast, but no place in particular; wherever the rides take me.”

“Well you’re in luck,” he said, “I’m on my way to Seattle.”

So I paid for my coffee and followed him out to the Volkswagen van he was driving. I noticed it had European plates. Turned out he was a Sergeant in the U.S. Army just back from Germany and on his way home to Seattle on an extended leave.

“Where you from?” he asked.

“Toronto . . . Canada.”

He gave me a surprised look. “That’s a long way to come. You look pretty young. Did you hitchhike all the way?”

I told him yes, except I took a bus from Toronto to Detroit, to get myself off to a good start. I said I almost didn’t get across the border. In fact, I got turned away, taken off the bus on the American side of the tunnel. But very early the next morning I walked across the Ambassador Bridge and a solitary border guard there let me across. I remember glancing back and noticed him looking at me with a strange smile as I walked off the bridge into Detroit.

I told the Sergeant-on-leave how after I got off the bridge I found myself walking into a run-down section of the city. Some years later I would realize I had walked into the black ghetto, but at the time I didn’t have a clue. It was still early in the morning and there wasn’t another soul in sight until I walked around the corner of an old, brick factory and found myself face to face with a middle-aged black man carrying a lunch pail. He stopped in his tracks and looked at me with wide-eyed surprise and said “What the hell are you doing here?”

He didn’t say it in an angry hostile way. It was more shocked surprise and concern. He actually took my arm and led me over to a bus stop. He waited with me there until the bus came. The destination was indicated over the windshield of the bus. I can’t remember what it said. But it was some location in downtown Detroit and he told me in no uncertain terms to make sure I stayed on the bus until it got there. So I did.

I’ve thought a lot about it since then. Being totally naïve and a babe in the woods so to speak, I had no idea at the time what had happened. But he must have known I was at risk – a young white guy and all – wandering around that neighbourhood, even at 8 in the morning. After all, it was probably his home turf. So he got me out of danger. He maybe saved my life.

In the years to come when in retrospect I realized what had happened, and would tell people about the time I hitchhiked across the States when I was 18, I would say “he was the first of my guardian angels. I could have died on that trip a few times.”

But in southern Idaho about a week after Detroit I just told the Sergeant-on-leave what had happened. And, tempting fate again in my impulsive way, I asked about his views on race relations.

“They have their world and I have mine,” was all he said, without expression, staring straight ahead down the highway.

Again, I had sense enough at least not to pursue the topic. But there was silence in the Volkswagen van for some time. Looking at the map now I would say we were on 80N, an interstate highway.

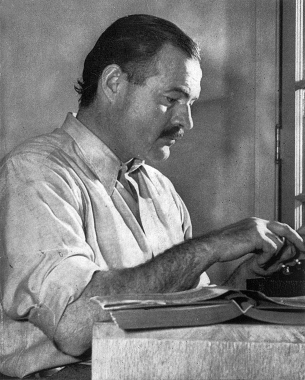

It was probably about 2 in the afternoon by then, a beautiful sunny day, and the news came over the radio in the van. It was a local station and the announcer read the solemn news that Ernest Hemingway, “the famous writer and Idaho resident” was dead, that he had shot himself early that morning in his home near Ketchum, in Sun Valley.

“That’s just a few miles in that direction,” the Sergeant said, motioning with his right hand at the rolling, foothills country on my side of the van. In my mind’s eye I can still see the rugged terrain of rocks and grass and a few trees rising to a large rustic house on top of the hill. For some reason I imagined at that moment that it might be Hemingway’s home. But of course it wasn’t.

“Really,” was all I said, as I kept looking out beyond the crest of the hill going by, into the sky, and vaguely wondered why a man might want to kill himself, especially one who had accomplished so much and gained such fame. In the years to come I would have no trouble answering that question.

We drove on. The Sergeant was anxious to get home, though I sensed something about it was bothering him. We reached Seattle late that night and he let me out downtown. As usual I sought out the local YMCA and got a room for the night. In those days YMCA’s had cheap hostel-type rooms or beds. I don’t know if they still do.

Of course I knew who Hemingway was. After all I think it was that year we studied The Old Man and the Sea in Grade 12 English Literature, along with Moby Dick. The point was to compare the thematic similarity of the two books, with the pursuit of the Great Fish being somehow reflective of man’s tragic state. I’d like to think I was already a Hemingway fan. I had grown up with him in a way. Winner take Nothing, a collection of Hemingway short stories, was one of my father’s favourite books, and around the house when I was a boy and my parents were together for a couple of years. I believe I read most of the stories in that book and enjoyed them on some level. That was when I was about 11. My mother and father split for about the fifth and last time, just after I turned 12.

Of course I knew who Hemingway was. After all I think it was that year we studied The Old Man and the Sea in Grade 12 English Literature, along with Moby Dick. The point was to compare the thematic similarity of the two books, with the pursuit of the Great Fish being somehow reflective of man’s tragic state. I’d like to think I was already a Hemingway fan. I had grown up with him in a way. Winner take Nothing, a collection of Hemingway short stories, was one of my father’s favourite books, and around the house when I was a boy and my parents were together for a couple of years. I believe I read most of the stories in that book and enjoyed them on some level. That was when I was about 11. My mother and father split for about the fifth and last time, just after I turned 12.

It wasn’t until I dropped out of first-year university in the winter of 1962-63 and moved into a cheap room in a downtown Toronto neighbourhood that I really started to get into Hemingway and other American writers. I read Faulkner, Wolfe, Steinbeck, Sherwood Anderson. I favoured short stories. My bedside book was a collection of short stories by Canadian writers, including Morley Callaghan. It included two of his gems, A Sick Call, and Last Spring They Came Over. I remember reading Callaghan’s autobiographical That Summer in Paris, about the time he and his wife spent with Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and others in Paris one summer in the mid-1920s, until they had a falling out over a boxing match in which the smaller Callaghan floored the much bigger Hemingway.

Anyway, I certainly had developed an appreciation for Hemingway by the time my father showed up one day at the rooming house quite unexpectedly. But that remarkable, troubled and tragic man with a passionate love and thorough knowledge of English literature greatly expanded my appreciation of Hemingway as a truly great artist. I was astonished by my father’s ability to deliver a perfect university lecture off the cuff, with extensive quotes from his favourite literary works to illustrate the points he was making. It came to him as easily as most people talk about the weather. Yet, like many men who grew up during the Great Depression, his formal education had stopped at Grade 8.

“There’s a poetry in Hemingway a lot of people don‘t see,” I remember him saying one day as we were walking down the sidewalk of a busy, downtown Toronto street on a sunny, Saturday afternoon, “a sense of profound resignation, like the way he describes the old soldier walking away from war in Under the Ridge, so simply yet so beautifully:

“‘His head was held high and he looked like a man walking in his sleep. . . I watched him walking alone down out of the war.’

“And his sense of the moment, and the perfect choice of words to go with it, like that line from Hills Like Elephants when the couple have been arguing a long time and the woman is finally fed up and says ‘Would you please please please please please please please stop talking.’

“Perfect, absolutely perfect. Hemingway is a very underrated writer.”

I was about to tell him how close I was to Ketchum the day Hemingway died, when suddenly without a word he took off running down the crowded sidewalk. By the time I caught up he was walking backward, virtually dancing with excitement in front of the florid-faced, grey-haired little man he had overtaken and brought to a sudden stop.

“Mr. Callaghan, Mr. Callaghan,” he was saying excitedly as I approached, “I want you to meet my son, Brian.

“Brian,” my father said, turning to me and using my middle name, the one I grew up being called, “this is Mr. Callaghan, Morley Callaghan.”

He looked so proud to be able to give me that moment. Somehow through a sea of people he had caught a glimpse of the back of an old head and immediately recognized it as Morley Callaghan’s. I can still see the author in my memory mind’s eye, his daily walk suddenly interrupted. I see him standing there quietly looking at my father with an expression of patient, though somewhat weary bemusement. I guess that sort of thing happened often enough to him. Callaghan struck me as sad, perhaps even profoundly resigned. I shook his hand.

“Imagine running into Morley Callaghan like that, just as we were talking about Hemingway,” my father said as he watched one of his literary heroes lose himself again in the crowd.

Yes, imagine. It wasn’t long after that my father disappeared again. He had said he might someday run away to Tahiti and live like Gauguin. But that’s not exactly what happened. He ended up in Hollywood where his last job was stocking shelves in a grocery store. He died in 1970 in a Los Angeles nursing home of Lou Gehrig’s disease. He is buried near San Diego in a cemetery with an artificial lagoon surrounded by palm trees. As he was being interred I stood beside his grave with his two little children, my sister and brother, Susie and David, and their mother, Daisy. I looked around at the virtual south sea island scene and said as his casket was being lowered into the ground, “you made it.”

After my father died I realized more and more over the years how much I love him, and miss him. We could have been such good friends, understanding each other so well, and Hemingway.

I play this game in my head, about timing and coincidence and fate: What if I had talked to my father and gained that deeper appreciation of Hemingway just 18 months earlier? I would have made a point of going to Ketchum. And what if I had arrived there a day earlier, knocked on his door and introduced myself as a great admirer of his work, like my father? I fantasize that Hemingway might have asked me in, that we would have talked, and I would have told him what my father had said about the poetic dimension of his writing, and about how he was a truly great artist. I imagine my youthful enthusiasm and admiration, with my father’s help, might have helped him find the will to live, and even inspired him to write again.

In my wildest dreams I like to think there’s always a new beginning on the other side of tragedy. At any event, my knock on his door would have interrupted a sequence of events leading to his death. And then, who knows what might have happened?

But, given his state of mind and paranoia about the IRS, he might have thought I was a government agent sent to spy on him. And then what? And why should Hemingway be glad to see someone from Toronto anyway? His time in the city in the early 1920s when he worked for the Toronto Daily Star wasn’t that good. He’d probably prefer not to be reminded. Who knows? He was pretty depressed by then, about not being able to write.

(Now that I think of it, what happened to the big fish after the Old Man tied it to the side of his small boat, and the sharks started coming, ripping pieces off it, was a metaphor for what was happening to Hemingway. Eventually all that was left was the skeleton of a great writer.)

None of that happened, of course. I didn’t go to Ketchum. I didn’t knock on his door. I didn’t tell him my father was his biggest fan and probably understood his genius better than anyone. I didn’t save Hemingway’s life.

I made it safely to Vancouver where I stayed in a room in a cheap hotel in the downtown east side. One night a man was stabbed in the hall in a fight outside my door. But what did I know? I was just a kid, a babe in the woods.

I didn’t die in Detroit. I didn’t die on the Tennessee side of the Ohio River, or in the parking lot of a truck stop in Missouri, or in Ketchum, for that matter. I didn’t die in Los Angeles. I am not buried in San Diego or Tahiti. I didn’t die in Indian Head, Alberta or in a speeding Porsche driven by a Jew-hating, neo-Nazi on the Trans-Canada Highway north of Superior on the way back to Toronto.

As fate would have it, I didn’t die lots of other times when I might have over the years.

No, for some reason I didn’t die in the summer of 1961, and haven’t died yet. And still I wonder why.

Hi Phil, As a parent I would have been extremely worried for my 18 year old son. Amazing, you do have nine lives. What an adventure you had. You remind me of my Angela taking off to Honduras and Africa and not blinking an eye or concerned at what might go wrong. She left without a worry and set out to rely on the good nature of people and that all is well with the world. Your sister Susan

LikeLike

Dear Susan, Actually I think by now I’ve used up those nine lives and then some. Thanks for the comment. Love, Phil

LikeLike

Lovely. Thanks, Phil.

LikeLike

Thank you too, David

LikeLike