It may have been August 30 when I first saw the new ‘park boundary’ and ‘no hunting’ signs posted on both sides of Cathedral Drive north of my property at the end of the ‘No Exit’ gravel road. I’d been away on a long trip and took a couple of days to rest up at home before going up that way with the tractor.

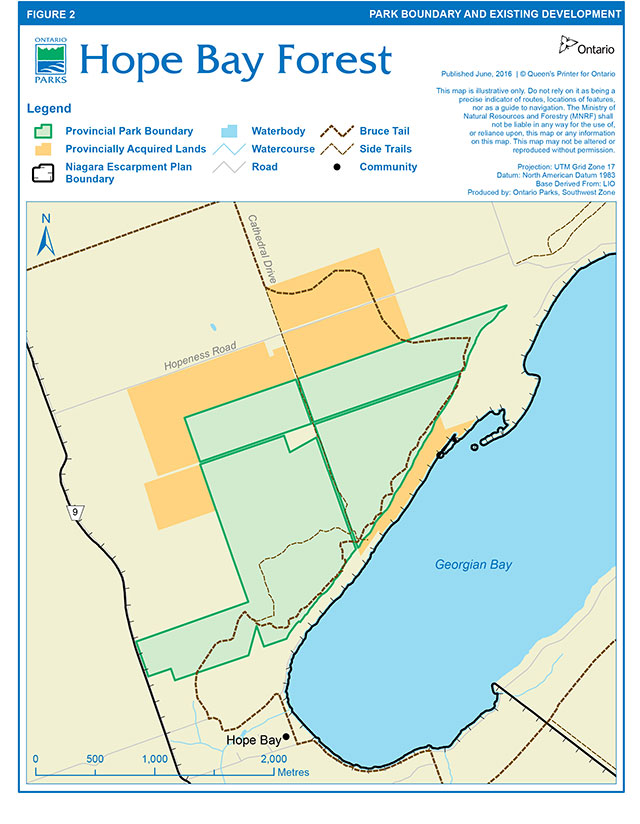

My first thought was the signs might have something to do with a possible out-of-court, negotiated settlement of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation (SON) land and water claim lawsuit. I’ve long believed a settlement of the multi-billion-dollar SON lawsuit would have to include a lot of land as well money in compensation, and that Hope Ness is bound to be part of it. The Hope Bay Forest Provincial Park (Nature Reserve) includes 353 hectares (873 acres). Other Ontario Crown land in the Hope Bay-Hope Ness area is of similar size and includes a large swath of Georgian Bay-Hope Bay shoreline.

My first thought was surely too much of a leap I initially told myself; but still, it was worth some research and a few phone calls.

And that’s how I found out, yes, there have been tentative talks at least; or, as a reliable source told me only, “there have been a few meetings.”

I was also surprised to discover that a three-judge, Ontario Court of Appeal panel has finished their deliberations regarding SON’s appeal of the initial Superior Court trial decisions two years ago. The appeal court decisions were published on the courts website August 30. That’s two weeks ago as I write this, and as far as I know, the news media has not picked up on and covered this important news.

The non-indigenous, local community has especially been kept in the dark over the years as the lawsuit has been slowly making its way through the legal process. Meanwhile, little has been done to prepare people for a day, and a negotiated settlement, that may be coming soon.

Late last year, a newsletter sent out to members of the two SON First Nations under the heading ‘Negotiations’ spoke of an intention to reach out to the two main defendants in the lawsuit.

“While we are pursuing our appeals, there may be a chance to start negotiations with Canada and Ontario to settle our claims.” In the past little progress was made, “but now we have a finding from the court in the treaty claim that the Crown behaved dishonourably towards us … We are reaching out to Canada and Ontario to invite them to begin those negotiations,” the newsletter said.

The appeal court also dealt with issues raised by municipal defendants who have not already settled with SON, including the Northern Bruce Peninsula and Southern Bruce Peninsula.

For example, the court has decided local municipalities are not responsible for financial damages SON may stand to get in connection with former Saugeen land now taken up by municipal roads. Under a treaty signed in 1854 surrendered land was to be surveyed, including into 100-acre farm lots, and the money put into trust funds for the benefit of the Saugeen first nations. But no provision was made for land that became road allowances under municipal jurisdiction.

The Ontario appeal court again denied the larger Aboriginal Title to the waters around the peninsula, as far as the U.S. border in Lake Huron; but in an unusual move the court has invited SON to seek title to a smaller area. That would most likely be an area known to the Saugeen Ojibway in the Anishinaabe language as Nochemowenaing, translated to English as ‘Place of Healing.’ That location is on the Georgian Bay side of the peninsula in the Hope Bay area.

Justice Wendy Matheson, who presided over the initial Ontario Superior Court trial, did not decide in favor of the larger Aboriginal Title; but she was much impressed by the cultural and spiritual evidence presented by elders from both First Nations that make up the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. They are the Chippewas of Nawash First Nation, with their home community beside Hope Bay, and the Saugeen First Nation beside the Saugeen River on the Lake Huron side.

“Joanne Keeshig testified about the role Anishinaabe women carry out with respect to water,” Justice Matheson wrote in her decision. “Like Karl Keeshig, she is a Third Degree Midewin and a member of a Midewin Lodge. She testified about the resurgence of the Midewin Lodge beginning in the 1970s. I found her evidence about her faith deserving of significant weight.

“Joanne Keeshig’s evidence also spoke of the Creator,” Justice Matheson wrote. “The Creator gave Anishinaabe women the primary responsibility to care for water. Anishinaabe women perform water ceremonies. In Joanne Keeshig’s view, if the Anishinaabe did not conduct water ceremonies, they would become disconnected from their purpose in life.

“Nochemowenaing was a very significant place from the Indigenous perspective, both as of 1763 and in more modern times. The waters at Nochemowenaing were and are believed to have healing qualities.”

The Court of Appeal judges took serious note of Justice Matheson’s written comments about Nochemowenaing, and also her inability to go further without a submission from SON during the trial. However, the court noted “SON asks this court to remit this alternative claim to the trial judge ‘for a judgment, after further evidence and submissions, on the question of Aboriginal title to a portion of the Aboriginal title area claimed.’”

The appeal judges agreed. “SON should not have to begin a new proceeding to determine this issue. The trial judge in this case is uniquely qualified to assess this request because of her long familiarity with the evidence and issues. The trial judge can devise a procedure that is fair to both sides, including further pleadings, discovery, and hearings that she deems necessary” to meet the legal test based on precedence.

Meanwhile, “the concerns of some of the parties and interveners about Aboriginal title to submerged lands and the public right of navigation cannot be addressed until the extent of Aboriginal title, if any, is determined.”

The multi-billion-dollar lawsuit was first filed in Ontario Superior Court in 1994. Initially, it focused on issues related to the way SON’s ancestors were pressured into signing a treaty that surrendered most of their remaining territory on the then Saugeen, now Bruce, Peninsula. Saugeen leaders were given one day to comply, or not, while Crown agents said they could no longer keep non-Indigenous squatters out of the territory. Just 18 years year earlier other Crown negotiators had promised to protect the integrity of the Saugeen territory on the peninsula if the ancestors signed a first treaty in 1836 that surrendered an even larger area.

The claim for Aboriginal Title to the waters around the peninsula was added later to the lawsuit.

After years of ‘discovery’ the Superior Court trial began April 2019. It ended July 2021 with Justice Matheson’s 200-page decision partially in favor of SON, in that it agreed the ‘Honour of the Crown’ had been brought into disrepute by the behavior of Crown representatives at the treaty negotiations; but Justice Matheson did not find in favor of the Aboriginal Title claim, and she also did not agree the Crown had a fiduciary (trust) duty that had been violated. SON appealed those decisions to the Ontario Court of Appeal.

Here is a link to that court’s decision: https://coadecisions.ontariocourts.ca/coa/coa/en/item/21689/index.do#_Toc144139795

Readers might want to jump to Part VI near the end of the document under the heading ‘Dispositions’ before tackling the rest.

And what of those signs that sent me on my quest for information?

The Hope Bay Forest Provincial Park, designated a Nature Reserve, now comes under the management of the Ontario Environment Ministry. It was previously the Ministry of Natural Resources responsibility. The park was created in 1985.

The Ontario government acquired about 2,000 acres in the former farm homestead community of Hope Ness after Dow Chemical decided not to go ahead with a plan to develop a huge quarry to mine the limestone bedrock for its magnesium content. In the mid-1960s Dow offered Hope Ness farmers $5,000 for their 100-acre farms. At the time “there was a farm on every hundred acres,” I was told when I came to live in Hope Ness in the spring of 1979. I bought one of the few houses that survived the Dow takeover because the farmer who owned it at the time refused the Dow offer. Most went for it, though it caused much bitterness in some families. Houses and barns were demolished, and families had to move.

The house and barns on the property where I live now on Cathedral Drive were saved because Dow had its on-site testing and research base here. And the Butchart family that had owned the farm were able to stay. They continued to live here after the farm became Ontario Crown land. Wilma Butchart (Tucker) and her son Cliff went to the Natural Resources office in Owen Sound to see if there was any way they could get title back to the farm. Eventually, they were able to get ownership of 5.9 acres and the house and barn and other outbuildings. The Hope Bay Forest Provincial Park/Nature Reserve now surrounds that piece of private property. What does the future hold? I wonder.

Earlier this week I contacted an Environment Ministry spokesperson to ask about the new signs. I was asked to email my questions. Had the park/nature reserve been expanded? Not that long ago in my eight years at the Cathedral Drive farm, I had seen deer hunters in the area recently posted with the new signs. Why now, and why the new signs? And I asked, is it because talks are underway for a possible, negotiated settlement of the SON lawsuit?

The answer came back: there has been no change, and no expansion of the nature reserve. It has always been there since the park was established. Hunting is allowed on other no-park provincial Crown land farther north.

As for talks about a possible negotiated settlement of the SON lawsuit currently underway? No answer. No mention at all.